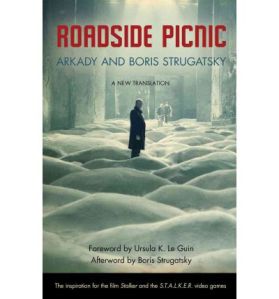

Roadside Picnic is considered one of the great examples of Soviet science fiction. First published in English in 1972, the book received new translation in 2012, along with a forward by Ursula K. LeGuin and an afterword by Boris Strugatsky about the struggles of getting the book through Soviet censorship controls. All three are a fascinating read.

The book has also resonated in the realm of pop culture, inspiring the Soviet film Stalker (1979) and the video game S.T.A.L.K.E.R. (2007). The story concerns a researcher paid to explore the site of an extraterrestrial visit and bring artifacts back to safe zones for study. However, he finds a growing temptation to return to illegally recovering the artifacts for sale on the black market as his life begins to spin out of control.

Roadside Picnic deals with the aftermath of six brief alien encounters known as Visitations, told through the eyes of Redrick “Red” Schuhart. The landing sites, or Zones, profoundly altered the known laws of physics, rendering the areas uninhabitable. Weird physical phenomena and alien plant life growing in the Zones can potentially maim or kill those that venture in. However, the danger and the value of artifacts left within the Zones tempt young adventurers.

Red is one of these adventurers. Drawn to a Zone in the town of Harmont (located somewhere in the British Commonwealth) soon after the Visitation, Red has settled down. Rather than entering the zone illegally and collecting as a Stalker, he works in a paid job recovering artifacts for the International Institute of Extraterrestrial Cultures. However, he finds the job intellectually stifling, with each excursion into the zone carefully planned and executed. Worse, the pay is a pittance of what he would earn as a Stalker, and the revenue stream is badly needed when he finds out his long-time girlfriend is pregnant.

Roadside Picnic is a grim novel, as it shows the lives of those that work with the Zone slowly crumble. Red in particular is shown to be a shell of his former self by the end of the book, utterly broken by the way working the Zones have adversely affected his life. Some of Red’s former coworkers show the same signs of strain, although from different sources, such as dealing with the overly restrictive bureaucracy of the Institute.

Honestly, the Strugatskys do a wonderful job at deconstructing the idea of “alien visit is a good thing for humanity”. One of the common tropes of sci-fi is the idea that humans are desperately looking for answers to their social problems. The typical first-encounter story of this era was that humanity had these problems solved by a technological messiah descending from outer space. But in Roadside Picnic, we get something of the opposite – the presence of alien technology makes our social problems worse. Yes, we get some benefits out of the artifacts that we pull from the zone (seemingly perpetual energy being one), but the benefit to humanity is negated by the squabbles we have over them: who gets to use the rare perpetual motion device? In a way, Roadside Picnic reminds me of a more deadpan version of The Gods Must Be Crazy.

The encounter is even more destructive to some people on a personal level. Red’s repeated exposure to the physical phenomena in the Zone have altered his genome, while seeing fellow explorers die beside him has left him a little unhinged. It’s also hinted that the people present in the Zones during the Visitations died horribly, die suddenly years after the fact, or have become something other than human.

Another point brought up is the inability of humanity to understand the artifacts left behind, or even the anomalies that occur all over the Zone. If we have no context to base our research on, does the information we gain from it even have use? Several characters in the book question whether or not we’re even using the artifacts in their intended manner. We could be very well be using a coke bottle as a hammer. The title is a references a parable given to describe this situation. A family makes a stop on the roadside for a picnic, and during their stay leave all sorts of litter and debris around. After the family leaves, ants swarm the picnic site, looking for food. Some of the debris they carry back to the nest may sustain the colony, while other litter is highly harmful to the ants. The ants have no way of knowing what is useful or not, except through trial and error.

In effect, Roadside Picnic questions whether or not meeting an advanced species is even good for humanity. Rather than answering with the traditional science fiction standard of “yes!”, the Strugatskys belabor the point that it’s not necessarily a good thing. Even if extraterrestrials were to give us the answers to everything, would we necessarily be able to understand those answers? Even if we did, would we apply those answers in a way consistent with fixing our social problems, or would we use those answers in a way that exacerbates the problem?

The answer the Strugatskys came up with makes a lot of sense, especially when viewed through the context of the Soviet system going into the 70s. The Soviet government was rapidly developing serious structural, combined with a failing economy that increasingly became concentrated in the military-industrial sector (David Hoffman’s The Dead Hand is a fascinating glimpse into the Soviet government’s mindset during this time period, and what I base a lot of this interpretation off of.). The result was a growing black market unable to be controlled by inflexible policy making at every level of government.

These trends are reflected in Roadside Picnic, which features a number of problems caused by the Institute. For example, the Institute barely pays a survival wage for explorers, while the overly bureaucratic procedures of the Institute focus on punishing the lawbreakers while ignoring the underlying cause of the smuggling problem. Viewed in this context, Roadside Picnic is highly subversive, and really explains why the Strugatskys had so much trouble getting the book into wide publication in the USSR. Boris Strugatsky’s retrospective on this is particularly interesting: the book was initially approved and published with only cosmetic alterations. However, when the book was selected for inclusion in a much more widely circulated anothology, the hammer came down from the censors. By the time the Strugatskys had pushed the anthology to completion, Roadside Picnic had been edited beyond recognition.

Soviet sci-fi authors are generally considered masters of the allegory, for good reason. While a story that could be viewed as too critical of the government might lead to imprisonment (an extreme circumstance in the 1970s, nowhere near as prevalent during the Stalin era), it was more likely to lead to a drain on the writer’s resources; an inability to publish the story and increased scrutiny in later stories was the usual result.

Roadside Picnic, in my opinion, is one of the better allegorical pieces to come out of the USSR in the late Soviet era. It addresses a lot of the problems that the common man might have faced during this era of Soviet history, but does so in such a way that even people in the West can identify with its protagonist. It speaks directly to the human condition, no matter the economic circumstances of one’s upbringing. I think this book is a must-read for anyone with a serious interest in science fiction, especially those interested in what it has to say about our present cultural problems.

The Strugatsky brothers are great. They did what science fiction is supposed to do. Fortunately, a lot of their work has been translated into English. They did a very good future history series also.

As far as whether it will be a good thing for us to meet aliens, I guess that depends on what kind of aliens they are! I don’t think Wells thought our encounter with the Martians was a particularly good thing for us. In fact, I think that science fiction has always been very ambivalent as to whether our encounter with aliens will be a good thing. But that is just another way of saying that science fiction has always been ambivalent about the effects of science on mankind in general. I think in the West, up until the 1970s at least, the attitude has been cautious optimism: there will be problems but nothing we can’t figure out how to handle. Most science fiction in fact was in the form of a problem: a novel problem was proposed and the resolution of the story was the solution of the problem. I am optimistic that any encounter by us with alien technology will be ultimately fall within the range of our understanding. I remember H. Beam Piper’s story Omnilingual, where the translation of alien texts was found to be possible simply because all scientific cultures have a common Rosetta stone which is the periodic table. All technological civilizations therefore should have at least some factual and psychological common ground, or else they wouldn’t be technological civilizations to begin with. Technological societies must have at least curiosity in common, or else they would never have noticed the existence and application of scientific fact to begin with. (Their motives for doing so may be different, but the curiosity must be there.)

So I think we will be able to understand new technology. How we handle it once we get it is another matter. In this regard, see my discussion on what will happen with newly-arrived longevity technology. In the end I think it is a moral question. If you have a proper set of morals you will be able to figure out what to pick up and what to leave alone.

I remember seeing The Gods Must Be Crazy. The tribe was living so close to the subsistence level that any change at all in their circumstances, even the introduction of a glass bottle, was highly disruptive to their social organization. Their response was to get rid of the technology, throw the bottle into the sea. In this regard, I am reminded of the Chinese empire and ocean-going vessels, as I discussed last time. Ocean-going vessels were highly disruptive to a society pushed to the limits of its development so they got rid of the ships, just like the tribe got rid of the bottle. The problem with handling things in this manner is that you will never be able to control your problems, you are only running away from them. When you need to be able to solve your problems you won’t be physically or psychologically equipped to do so. And when your African tribe and your empire do not know how to handle the bottle or the ship, like the West knows, the West hands you your head. As I said, you have to know what to pick up and what to leave alone, and you can only do that by understanding what you are dealing with. There is a difference between knowing and understanding on the one hand, and actually using something on the other hand. Knowledge is good because it enables us to make informed decisions, and our morals tell us what can be properly and safely used and applied. No attempt was made by the tribe to understand what the bottle was or how to control it. If your problem is that there is only one bottle, once you understand how to make a bottle, you can make as many as you like. Because as we know, the gods are not crazy; bottles actually can be made to serve a useful purpose. You may very well decide to throw away the bottle after you understand it, but that will be an informed decision, and you can make another bottle if you find later down the line that you need one.

I don’t think that curiosity alone is enough of a common ground to build an interspecies understanding. Communication is a huge issue, and while the idea of using the periodic table as the basis for figuring out an alien language is kind of neat, the true likelihood of that happening seems fairly low. I’d say it’s somewhat analogous to learning the Japanese language and culture from studying a Japanese edition of the periodic table. You might learn some things about the culture from it based on its presentation, but by itself (and only by itself), you’re not going to learn enough to get any true insight. You need a lot more common ground to really understand how other species think and interact.

The second problem that the Strugatskys set up is that the artifacts left behind in the Visitations are so far removed from what we know of physics that they may as well be impossible to understand. We might be able to figure out some useful things that we do, but their method of doing is essentially a black box. We have no context for how they form or operate, so while we might be able to see Point A and Point B, we have no idea of how to connect them. We can find uses for the artifacts, but we have no context for understanding how to operate them. It’s a slightly different situation from knowing and understanding, in Roadside Picnic, we know, but have no way of understanding.

Ultimately the disruption to society before an item can be understood and contextualize may be so great that holding onto it until knowledge has been acquired from it is impossible. In Roadside Picnic, the use of most items recovered from the Zone is very disruptive to society, and yet exploration and attempts at understanding continue, despite the fact that they’re destructive on a personal and societal level. You can’t place these artifacts into a moral context until they’re used, and their use can be destructive from the very beginning. When curiosity kills the cat on a regular basis, is it worth continuing to be curious about those things?

Even the lowest life forms constantly explore their surroundings. According to Aristotle, man is by nature a social animal; I think he is also by nature a curious animal. So we really can’t help outselves anyway. As far as curiosity killing the cat, we all die anyway. I think it is better to die on the frontier trying something new than to die of a squalid old age. It is the frontiersmen who are seen in the history books as the benefactors of mankind, not the people who die in bed without having risked anything. There cannot be any gain in knowledge without an attendant risk. Fire in its time was a great innovation, but I am sure there were those who said we should not fool around with something that can burn us. But we know there were people stupid enough to use it anyway, because here we are. Human stupidity has both advantages and disadvantages. See, for instance, R.A. Lafferty’s “Eurema’s Dam.” Fortunately, the lazy and stupid people always win out over the intelligent cautious people in the long run. This is why people will jump on longevity as soon as it shows up; they won’t do much with it but they will definitely use it because they won’t bother to figure out the consequences.

If you don’t do it someone else will, and when they come knocking on your door, you will be in for a bad time. The main reason why the Spanish Crown financed the great Columbus was not because they had any particular faith in his theory, but because they knew that if they turned him down he would try to interest another kingdom in his project, with possible bad consequences for Spain. That is why here in the United States the only Spanish queen anyone knows is Queen Isabella; I am willing to bet that the vast majority of Americans don’t even know that there is a current incumbent of that position.

It’s true that we explore our surroundings, but we’re able to put our observations into context. For example, fire is something we can witness in nature all the time, and we’re able to put that into a socially beneficial context – lots of fire hot, controlled fire warm. Even with our most destructive sciences, such as nuclear sciences, we have some basic understanding of what goes on behind it, and we can also contextualize it from the same standpoint of fire – lots of uncontrolled chain reactions bad, controlled chain reactions good. New technologies are fairly logical outgrowths of existing technologies, and we have a basic understanding of how they’re intended to be used, even if that use may change rapidly or have unintended consequences. They’re all things we’ve dealt with before. So when Columbus says he’s going to sail to India and the Spanish Crown funds him, it’s because they were funding an available and well-known technology that they’d been slow to adopt previously, and had already lost out to their neighbor Portugal with securing trade routes.

However, in Roadside Picnic, there is no foundation for understanding new technologies that come out of the Zone. We can experiment with them, but we don’t have any idea of what they do, exactly. We can test them and maybe get some results and find something useful, but on the whole it seems that playing around with it is dangerous for humanity. I think one of the ideas that permeates sci-fi is that humans are uniquely good at reverse engineering stuff, but that draws from our experience of reverse engineering existing technologies, with already understood concepts. When you apply that idea to alien technology that’s centuries or millennia ahead of our own, the idea that we’re able to reverse engineer and learn breaks down.

I’m not saying to just leave the stuff in the Zones out to rot, by all means collect it and make sure it’s safely stored, but until we can put context on the artifacts, say “aha, I’ve seen that effect from an Artifact”, they should by all means be left alone. It’s like using a small bomb as a sledgehammer. It might work well as a sledgehammer for a while, but eventually we might hit it wrong and have it blow up in our faces.

I would certainly agree with you that you need to study things before you try to use them. With any kind of technological development, you should make haste slowly. If you look at the thalidomide case, for instance, the drug was discovered in 1954, and thrown onto the market, where it was used until the early 1960s, when the birth defects were discovered. Then they took it off the market. However, now it is back on the market as a treatment for multiple myeloma and other diseases. If they had performed adequate testing to begin with, the problems might not have happened. My point is that there is a difference between adequate testing and evaluation, on the one hand, and just throwing the bottle into the sea on the other hand.